“Makiri” can trace its roots to an essential knife of Ainu people in their hunting life and was transmitted by northern-bound ships to Noto peninsula from Ezo area where a tool culture was alive. The fishermen in Noto bring this small knife on their waist because of its simplicity, durability, usability and its cutting force as a tool to be used in the “wilderness”.

As well as it has been used to clean a fish, it also has supported and protected the lives of the fishermen by being used for the maintenance of the fishing net, removing things tangled in it, and sometimes cutting off the ropes winded around the body on the ship in a storm. Makiri, with which almost all of the works on the sea can be done, is so useful in many outdoor activities such as camping, fishing and hunting.

Fukube Kaji, a blacksmith of tools in a small area in Noto peninsula, continues to create this small knife since its founding in order to let people know about Makiri culture which has become rooted into the life of Noto. The way of creating tools with their spirits shows their pride as a blacksmith of tools supported by the agriculture and fishery in Noto.

Powerful cutting force and bendability by making full use of materials

Watetsu is obtained by Tatara furnace, a Japanese traditional ironmaking process using iron sand and coal. The main feature of Watetsu is its softness as material since it is made by iron sand, in contrast to wrought iron made by iron ores. It is also called “Hocho-tetsu (knife iron)” because of its shape, and it has been used to make blades and agricultural tools all over the country since early times. Today, however, it’s become very rare iron only made in Nittoho-Tatara, in a part of Izumo district in Shimane prefecture.

Fukube Kaji uses only Watetsu as a material for making Makiri because it is high purity iron, there are the layers of soft iron and hard iron with a very high carbon content, it has little grain boundary and the inside of the iron is resistant to rust. For example, for base metal of a knife, we reuse the Watetsu used in a building of more than 150 years old such as lattice windows of an old warehouse in Noto. Watetsu is hard and resilient, called “high quality natural composite material”, and is the most suitable material for base metal of blades.

Watetsu, a very admirable material, and the practicality of Makiri. Combining them very well requires the technique of blacksmith of tools supporting the lives of the people in the area for many years. The Watetsu of good quality is obtained by forging unstable Watetsu and removing impurities. Pine charcoal is used for forging because it enables to control temperature finely. Every blow and every sharpening action are full of technique and knowledge obtained through the making and repairing process of agricultural tools and knives based on the lives of people.

Trenchant blade for survival, made by blacksmith of tools in Noto

With a good maintenance, you can see how long cutting force of Makiri lasts. In particular, you can enjoy sharpening “Magomitsu-bessaku” and “Magomitsu-saku”, made of Watetsu, because their base metal is soft despite the hardness of their blades.

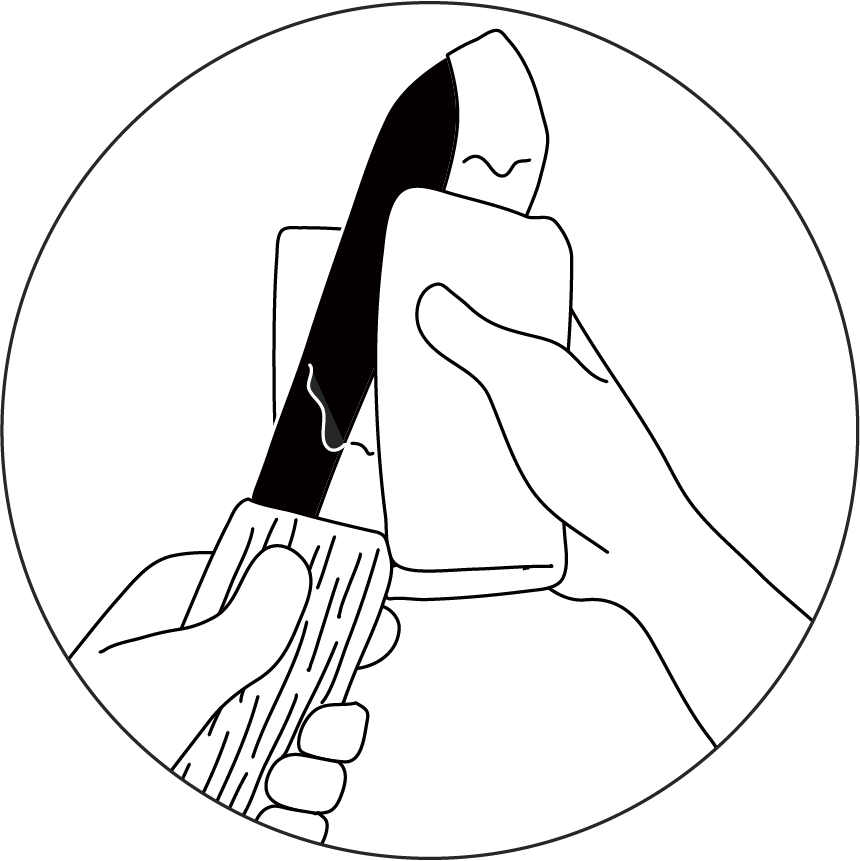

Salt and acid may cause getting rusty. Make sure to wash your blade after use. Dry it very well with a dry cloth after washing.

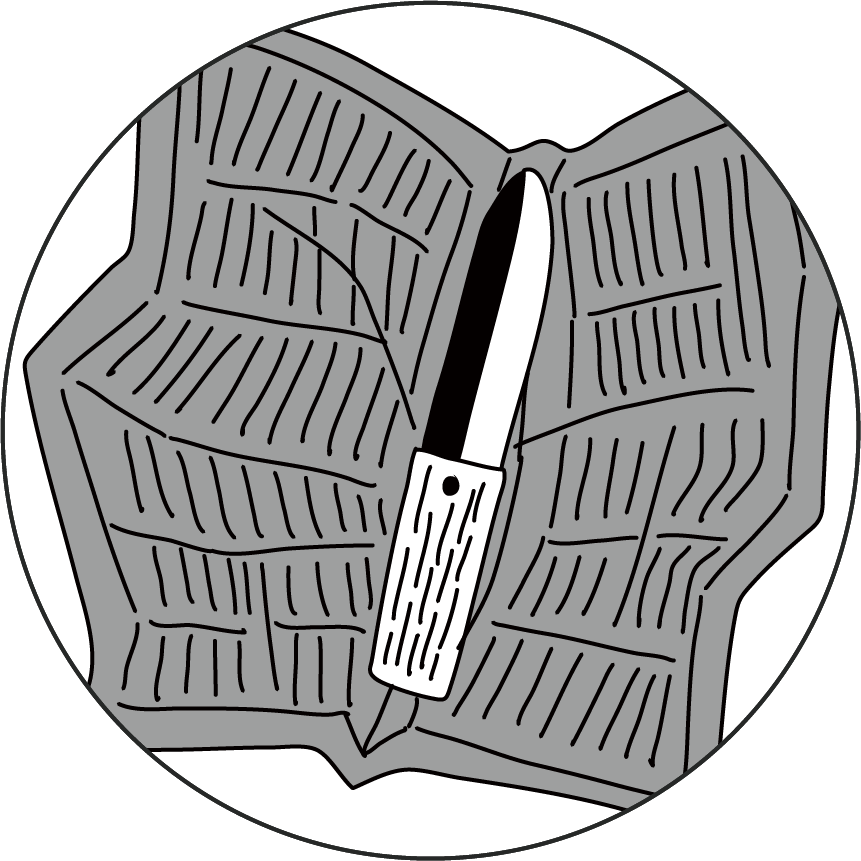

Treat the blade with oil for blades such as camellia oil after drying. This will help prevent it from rusting. If your knife is not going to be used for a while, wrap the knife in newspaper and not storage it in highly humid place.

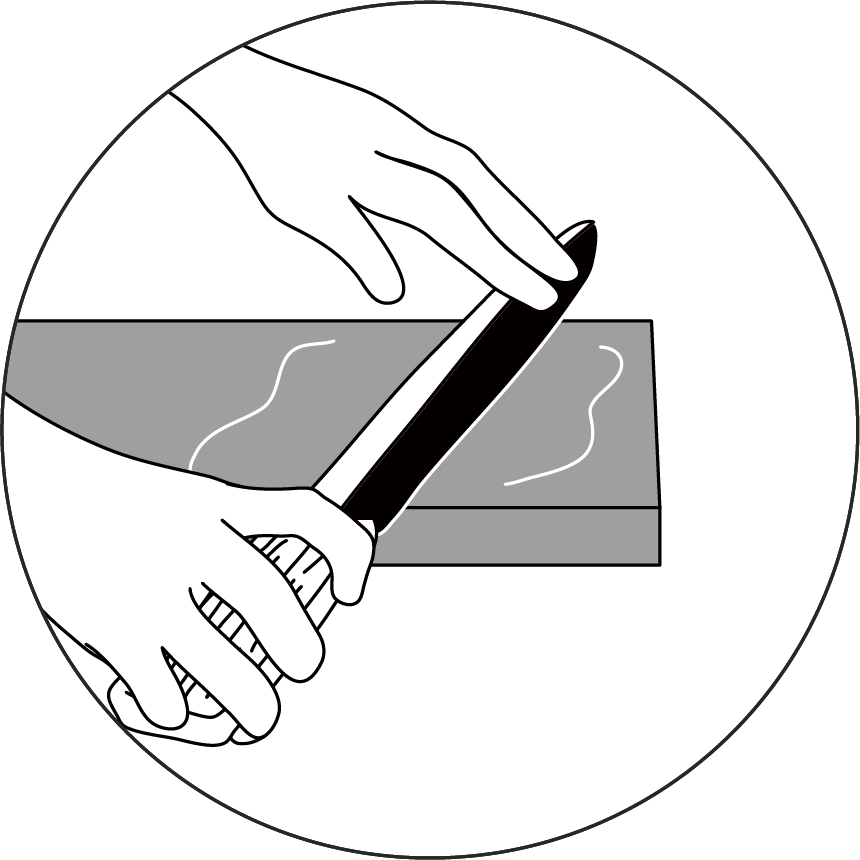

The key to sharpen well the Makiri of a single edge is to place the surface of the edge tightly on a sharpening stone. In order to sharpen the knife better, it is recommended to use three types of sharpening stones with different grits; a coarse stone, a medium stone and a finishing stone.

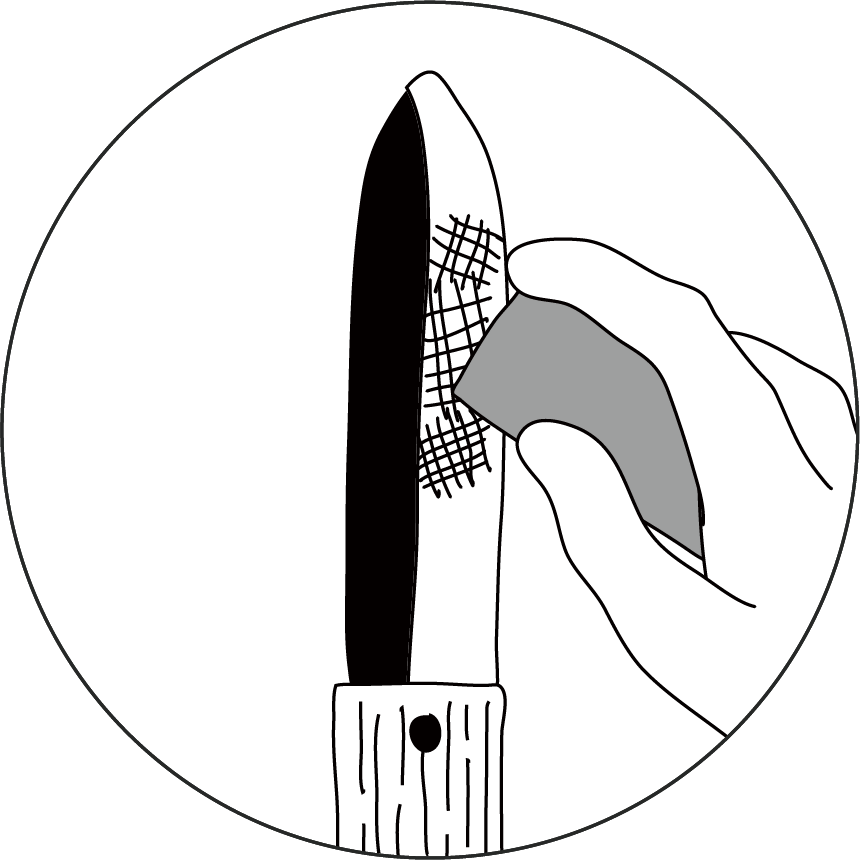

If you find the rust on the surface, scrub off the rust as soon as possible using rust remover. Remove the rust on the blade edge by using sharpening stone.